Weekly Market Commentary

So far this year, forecasts for a recession or a soft landing have failed to materialize. What is a soft landing? Economic growth slows, the rate of inflation slows, but the economy stays out of a recession. In other words, the economy is not too hot or too cold.

Instead, there has been no landing. Last month, the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysts reported that Q3 Gross Domestic Product (GDP) expanded at a robust 4.9% annualized pace.

But we are in a new quarter. Payrolls grew by a modest 150,000 in October, and the unemployment rate rose from 3.8% to 3.9%, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

With the jobless rate in a gradual upward trend, are we headed into a much-elusive recession? Or is the much sought-after soft landing, the most likely scenario?

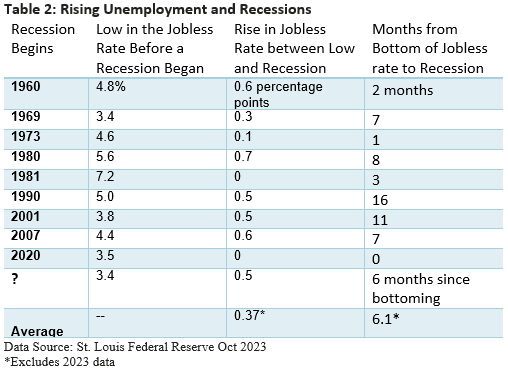

Table 2 highlights the correlation between a rising jobless rate and a recession.

Let’s use the 1960 recession as an example. Prior to the start of the recession, the jobless rate fell as low as 4.8%, it rose 0.6 percentage points before the recession began, and it took 2 months between the 4.8% low and the onset of the recession.

The average rise in the jobless rate that eventually led to a recession: 0.37 percentage points.

The average number of months from a low in the jobless rate to a recession: 6.1 months.

The unemployment rate is up 0.5 percentage points since hitting a cycle low of 3.4% in April. Past experiences suggest that the odds of a recession next year are rising. But this model isn’t ironclad. In 1986, the unemployment rate rose from 6.7% to 7.2% without an ensuing recession.

Fed Chief Powell has repeatedly said he believes economic growth must significantly slow to bring demand for goods and services back in line with supply. This would help foster the conditions needed for price stability.

A big slowdown in growth would include an upward drift in the unemployment rate. That said, the Fed has powerful tools that can stimulate or slow the economy, but it can’t fine-tune GDP, unemployment, or inflation.