“The new Administration is in the process of implementing significant policy changes in four distinct areas: trade, immigration, fiscal policy, and regulation. It is the net effect of these policy changes that will matter for the economy and for the path of monetary policy,” Fed Chief Jay Powell said in prepared remarks Friday afternoon.

There is plenty to unpack in Powell’s comment, but we want to concentrate on what is sparking the volatility in the market, and Powell touched on a couple of points.

President Trump’s one-month delay of levying a 25% tariff on goods imported from Mexico and Canada expired last week.

Trump briefly restored the tariffs, then postponed them for an additional month for items included in the USMCA between the U.S., Mexico, and Canada.

The USMCA replaced NAFTA, a trade agreement in effect between 1994 and 2020.

Investors are fretting over tariffs amid worries that they will raise prices at a time when inflation remains elevated.

And there are concerns that nations subject to tariffs will raise barriers of their own, which could hinder U.S. economic growth and exports.

Additionally, economic uncertainty arising from policy changes may discourage some businesses from expanding or retooling until the situation stabilizes.

In other words, investors view the tariffs as economically disruptive, leading to market volatility.

According to U.S. Census data, the two biggest U.S. trade partners are Mexico and Canada.

Clouds on the horizon

“Could we be seeing that this economy… (is) starting to roll a bit? Sure. And look, there’s going to be a natural adjustment as we move away from public spending to private spending,” Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent said Friday on CNBC.

“The market and the economy have just become hooked. We’ve become addicted to this government spending, and there’s going to be a detox period,” he added.

Investors perceive events through a narrow lens: Will they gain or lose? Will it help or hurt stocks? That is how we frame the conversation.

Budget cuts, federal layoffs, and layoffs of private government contractors, coupled with economic uncertainty regarding tariffs, could put the brakes on the economy over the shorter term, as Bessent conceded.

That is what the market is responding to (a discussion of government spending/waste falls outside the scope of this analysis).

More common than you think

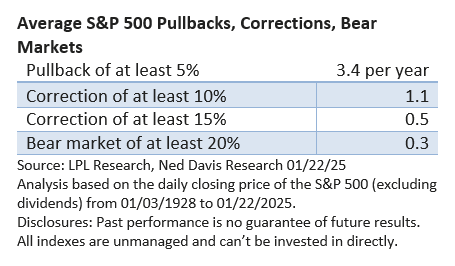

We recognize that pullbacks occur from time to time. The S&P 500 Index averages a pullback of at least 10% about 1.1 times per year.

We haven’t undergone a 10% peak-to-trough decline since late 2023.

Since the S&P 500’s peak on February 19, the index is down 6.6% through the most recent bottom on March 6 (MarketWatch data). So far, the magnitude of the pullback is far from unusual.

In the past, pullbacks and corrections have been driven by recession fears, higher inflation, trade issues in 2018, the fiscal cliff in 2012, overseas challenges such as the European debt crisis, and more.

In other words, corrections don’t happen on their own. They need a catalyst.

While stocks are modestly off their highs, the consensus that the economy won’t slip into a recession has helped cushion the downside.

As with prior pullbacks, we can’t pinpoint the bottom.

The lucky few that may call it will find that consistently predicting market tops and bottoms will be out of reach. Simply put, no one knows the future.

What we do know is that broad market indexes have a longer-term upward trend, and market declines eventually run their course. Historically, the patient investor has been rewarded.